The strikes in Hollywood were one of the biggest stories of the year. They kicked off when the Writers Guild of America (WGA) hit the picket lines on May 2 after unsuccessful negotiations with the Hollywood studios and streaming companies. The writers’ strike ended up running until September 27, with actors later joining them in a strike of their own. It became a key moment not only in the surge of labor activism through 2023, but also the AI storyline playing out across the world.

There were many issues on the table in the negotiations, but given Silicon Valley’s decision to unleash generative AI tools on the world and amp up the hype around them, they also became central to the demands of the Hollywood guilds. Writers could see that more powerful AI tools could have serious implications for their profession, as streaming services and other technologies did previously, and that it wasn’t necessarily because the technologies were game changers, but that the studios would be able to use them to further shift power dynamics in their favor.

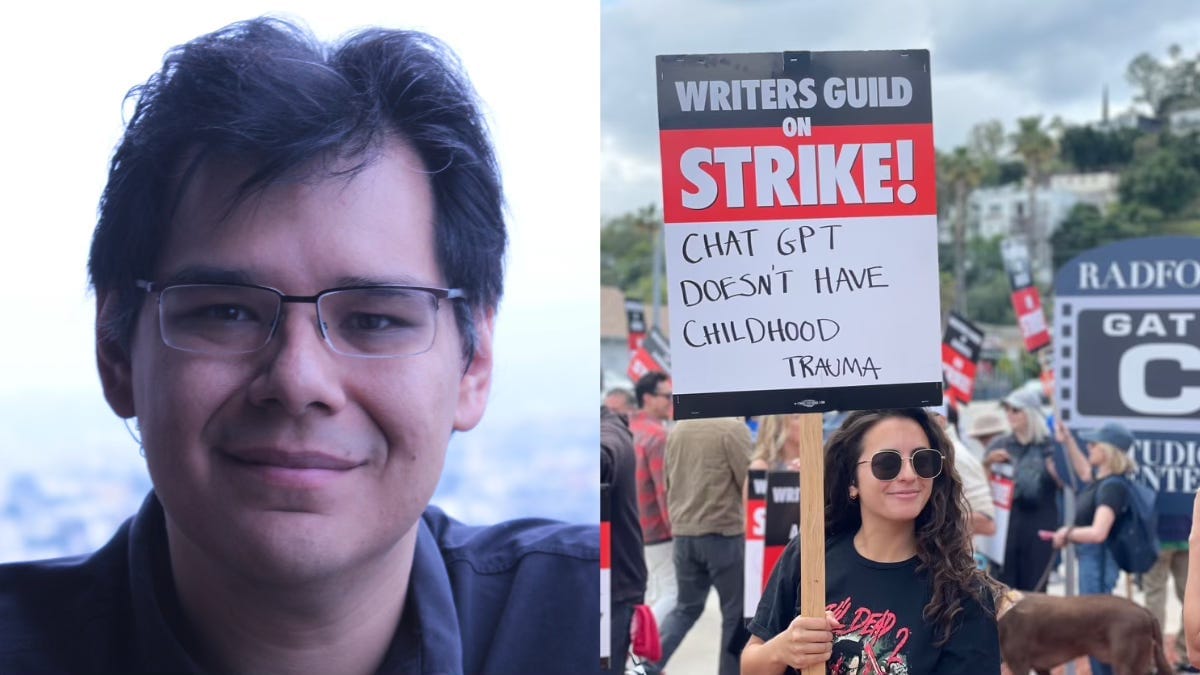

As 2023 comes to a close, I thought it would be a good opportunity to revisit the writers’ strike. To do that, I spoke to John Lopez, a writer, producer, and member of the WGA’s AI working group. We discussed the importance of dealing with the AI issue in this contract cycle, what the Guild was looking for, and how workers can push back against these technologies.

Interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Did it surprise you that AI became one of the major issues of the WGA contract negotiation and strike? Did you think the threat was overstated or it got the attention it deserved?

Some of the other members who were less AI focused might have been surprised at first, but then it quickly became obvious that this was one of the crucial existential issues for the Guild. The way I got to the AI working group is that I had been aware of this stuff because I had a lot of contacts and friends in Silicon Valley who are working on AI and had been showing me the various forms of what we now call generative AI, but I hadn’t been actively communicating with the Guild about it. Then ChatGPT came out and I knew that was a weird surprise move on OpenAI’s part because they had always portrayed themselves as somewhat interested in research, and then they revealed themselves to be a commercial company. When I saw that, I emailed friends on the board and said, “Do we have anyone working on this? I think we need to address this in this contract cycle. I don’t think we can wait three years to do it.”

In the WGA, when someone speaks up, your punishment is to be put to work doing it, so I got put on a committee that had already been started. I don’t know the exact origins of it, but it had members like Deric Hughes, John August, who’s obviously very technologically oriented, and someone who’d run for the board, Dan Robichaud. They had been pushing for this, and it happened. At first, it was a little bit theoretical, then when ChatGPT debuted, it became very practical. John Rogers was a physicist by training, he had a lot of experience with upper level maths, so he really got right away how these things are built. I shared all the insight I had from professionals and colleagues working in the AI industry with the Guild, and then everyone else had just been following it on Twitter. I mean, sometimes we would just be swapping Twitter links, TikToks, anything we have that was real-timing what was coming out of the industry and where we thought it was going.

We really quickly knew we had to address this now. There’s always a fight for prioritization in any contract negotiation over what you’re going to try and win, but the more we dug into it, the more we experimented with ChatGPT and Bard and Claude, we knew we needed to do this now because in three years, it’d be too late. The Writers Guild is often cognizant of how past negotiations sometimes don’t anticipate technological progress. There’s always this big debate in Hollywood media about, When did you fight for streaming? And when did you fight for the internet? I would say the Writers Guild is one of the more forward-thinking guilds in terms of trying to anticipate that. It’s always hard to guess where technology is going to go, but we don’t want to get caught unawares. So it became a big deal, and then it was talking to the more senior leadership and explaining it to them. They got it right away. We had a big call with them and went through everything we learned and it was just kind of an eye-opening moment.

I should stress, it’s really difficult to accommodate new demands into a bargaining situation. I remember being on the strike lines one day and running into Chris Kaiser because all the negotiating committee members would be on the lines and just talk to people. I said, Chris, you may not remember me because we Zoomed, and I was with another member of the AI working group. And of course, he knew us and he’s like, Thank you for alerting us to this and making sure that this is a priority.

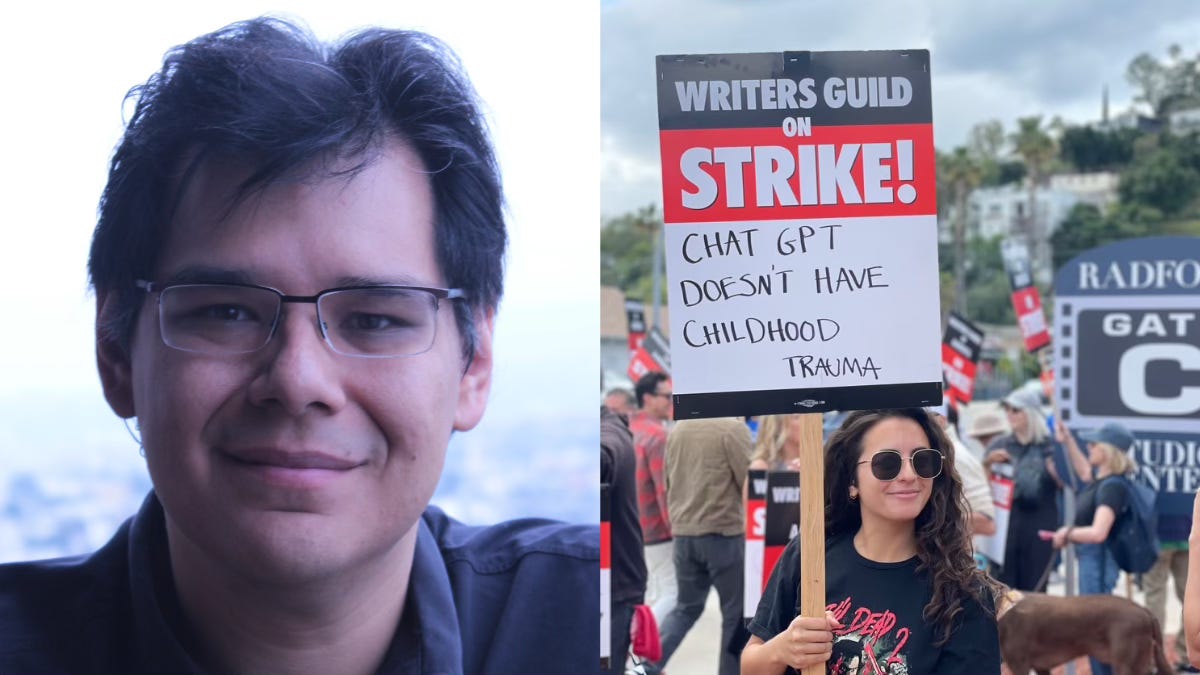

When you get on the strike lines, right away, it was instant. It’s visceral for writers, especially when you find out it’s your work being used as the training data and that the ability to mimic you as a writer or an artist is something that the AI companies are bragging about. Within a few weeks of the strike actually happening, I started seeing it on the lines. People’s signs, were just like, “Fuck ChatGPT” or “ChatGPT doesn’t have childhood trauma.” I was definitely surprised by that, but in a good way.

It seems like there was a happy coincidence in the fact that ChatGPT was released in November 2022, meaning there was enough time for people to see what it potentially meant and could still influence what was going to happen in those negotiations. There is this perception that there wasn’t enough done to ensure that the streaming model didn’t upend the business model of the industry and writing as a profession. It felt like this was potentially seeing something coming down the pike and trying to get ahead of it.

We know we were lucky, and we wanted to take advantage of that luck. If ChatGPT had been held, we would have missed our negotiating cycle and then it would have been three years of the studios playing around unregulated — because I think the thing that people have to remember with AI is that you can talk about what it is or whether it thinks or whether it’s creative (I don’t think it’s creative), but whatever it is, I don’t think anyone outside of Silicon Valley really understood where it was going until it launched. Laws are not written for these things; they’re not constructed with the mechanisms of these machines in mind.

If it had been even six months earlier, that would have given the studios much more time to start forcing it and establishing facts on the ground that then you’re negotiating against. We’re also aware that like in the broader context of labor, this is something every union, every working person, whether or not they have a union, has to contend with. So we’re planting a flag. We know this stuff is going to be used, there are elements of it that I find immoral and elements of it that should or shouldn’t be used or regulated, but it’s not going away. So we need to make sure that the force of this stuff is channeled as much as possible in a way that protects real human beings and people in our industry — creative people that I do not think the people building it in Silicon Valley or the big tech companies really care about or think all that much about.

That human angle is essential. In the actual negotiations, what were the key concerns that writers had about the use of AI in their profession?

The main concern was how it could be used as a cudgel to take away money or work from people. First off, the key concern was what we thought was the easiest ask: that a writer is a human being. This is a creative industry and ultimately you have to ask yourself: Why are you creating? Why are you making shows? Yes, to entertain people; yes, to get people butts in seats, as they say, for theaters. But it’s this weird combination of commerce and art, and there’s still the art part of it. Art is about humans communicating to other humans. The human is not just a byproduct of the system; the human is the system. And we wanted to preserve that for the people doing it. So we thought “writer as a human being” — that should be easy. It was not easy. It took a long time to fight for that.

The second was this notion of paying a writer less for the same amount of work, but using the outputs of generative AI as an excuse to do so. They might say, Oh, your job is so much easier now because this thing can just output text at a rate no human being ever could. I like to say, the act of writing is not typing. If writing was typing, it would be easy. The act of writing is thinking about what you have to say and how you want to say it and how to say it in the most dramatically effective manner when it comes to screenplays. Honestly, for me writing is a lot of staring at a screen and hating myself and then rewriting and thinking things over and then finally getting something that works, and then talking to an actor about it or talking to a director about it, and talking to a producer about it. Writing happens on set, writing happens in post-production when you’re the showrunner and you’re looking at the edit and you see that if you put two scenes together, they no longer make sense. We have to massage it in a way that doesn’t destroy the story. This is all writing. So the idea that somehow a thing that automatically outputs meaningless, randomly generated text that kind of looks sensible is going to make this job easier for us is really not the case.

I have tried so hard to use these things in my process to make it better. So far, I have found very limited applications for them, and this is not even to get into the moral dimension of how these things are built. So what we were concerned with is the studios would look at that and say, oh, you can output 60 pages of text in 20 minutes now, so the what you do is no longer valuable, so we’re going to pay you less. The exact mechanism of that was the studio will start by generating a script and giving it to a writer to rewrite. Anyone who’s done screenwriting or many types of writing will know sometimes rewriting from a really bad script is worse than starting from a blank page. There’s often a case where writers are brought on to rewrite another writer. Avoiding the issue of whose vision was right or wrong, oftentimes screenwriters will just start from page one, even if there’s a fully written script. It’s just faster and easier and better as a writer to not try to change what this other writer was doing, because clearly, it’s not answering what the studio wanted. We wanted to avoid that obvious trap.

There were a couple of other things, like forcing writers to use AI when they don’t want to. The Writers Guild and a lot of the guilds in Hollywood are very protective of the processes by which we create this entertainment. That’s our expertise. The executives who are cutting our checks, they don’t really do this, they don’t have an appreciation for it. And writing especially, it’s very easy for someone to say casually, oh, I can write, look, I typed this up. Therefore if I can do it, you should be able to do it like that. But that’s not the wrestling. That’s not the time spent. That’s not really what you’re doing. Again, what you’re doing is typing versus writing. Some executives definitely value and treasure writers. But the ones who cut the check sometimes look at writers and writing as very fungible and very disposable and very interchangeable.

What I’ve noticed so far with the writing quality is that it’s not good. If you know how these models are constructed, they tend to create an average. They tend to create the bland, the median, and oftentimes in Hollywood, what you’re trying to do is push against that, you’re trying to push forward creative frontiers. So being told to use something that is automatically going to drive you towards average or towards cliche or towards plagiarism felt like something that should be in a writer’s control. So that was another big one.

The last one is where you get into the moral dimension. Unfortunately, it was the hardest as it seems to have been with both SAG-AFTRA and the DGA, which is the intrinsic moral right of who gets to use a writer’s work to train an AI. Where does that right belong? Who gets paid for that? Who asks permission for that? It is my personal conviction, and the guilds have put out many statements about this, that it’s the writers. It’s very fundamental. Do you want your work to be used to train an AI? Well, that should be your decision. That should be a matter of consent, compensation, and consultation for the individual writer. Just because you sell a copyright or you because you don’t own the copyright because you did work under what’s legally known as “work for hire,” that doesn’t mean writing one script gives a studio the right to then train up your voice and your style and your creativity. Basically, you — your identity in an AI.

When we talk about these technologies, sometimes people just say, Oh, the robots are going to take our jobs or our jobs are going to be eliminated. But what you’re talking about there is not just the AI coming in and all of a sudden the writers are gone, but actively using the AI or the excuse of having generative AI systems to change the way the work is done in such a way that disempowers and devalues the work that writers are doing. It’s understandable why writers would want to stop that, but I think it’s in the interest of the general public to want to stop that as well.

In a weird way, the AI industry is shaping up to be an extraction industry, kind of like fossil fuels. I think one economist described the way AI systems work as using fossilized labor and turning it into a form of gasoline. Climate change is obviously horrible, but for better or worse, the dinosaurs are dead. When we’re running cars off of their bones, we’re not actively harming them; we’re actively harming ourselves and the planet, which is another issue. But in this case, you have living, working writers whose work is being fed into machines and synthesized into a weird form of fossil creativity that now is powering all these image generators and chatbots.

We humans have really bad intuitions about large numbers and just about how much stuff there is on the internet, so every time you get something useful from an AI system, someone somewhere typed something very similar to that. The AI sucked it up, reconfigured it based on your prompt, and then fed it back to you. You’re having a conversation with someone across time and space, and that person is not getting paid for that, is not getting attribution for that, and was certainly never asked if that was okay.

The Writers Guild and the writers who are members of it went on a months-long strike to get a better deal than what they felt the studios were initially offering. Obviously, there were many things that came out of that, but on the AI question, what did the WGA win in the contract? And are those wins important?

A lot of amazing things. We won that writers are human beings. That would seem like a basic one, but that’s an important principle going forward. We got that a writer can’t be forced to use AI, that an AI cannot be the originator of a project, that if you’re going to pay a writer and have them use AI and you guys agree to it and it’s mutually conducive to both of you, you’re still going to pay the writer the same amount of money. What we’re trying to do is remove the profit incentive to wholesale adopt suboptimal AI methods because it saves money, because so far, in my experience, the quality that these things put out is not really good. Maybe they’ll get better. I have theoretical reasons to believe that it’s not going to get better as fast as people think, and so far that’s been borne out.

The last thing was simply to agree to disagree on the training data. We reserve our rights and we’re hoping to get that message championed by Congress, by the Copyright Office, and in the courts. If it comes down to our contract, then through further arbitration. That principle is something that the Writers Guild fought very hard for, and that principle is something that is a continued fight that everyone needs to be fighting for right now to protect themselves. Whatever the promise these systems have — I would say some of them are very overblown and overhyped — we need to ensure they don’t cause more damage than benefit.

You don’t want to roll out AI systems just for the sake of rolling out AI and then, in the process, tear up our well-functioning society, which has felt like the modus operandi of Silicon Valley for a long time. They enter an industry or an arena they don’t really know anything about or why it has developed the way it has, then ripp up the organic structures. They are replacing them with digital structures that tend to accrue the profit back to them, then make a mess of things and then people go along with it because there’s this sense of like, Oh, wants to be against technology? Technology's amazing. It tech will save us. Obviously, you know that it won’t save us.

I live in LA. The big metaphor I always think of is that LA used to have one of the world’s greatest public transportation systems in the 1920s, the Red Cars. It wasn’t perfect, but you could get from downtown Los Angeles to Venice in 40 minutes on a trolley. But then cars took over. There was a moment where the city of Los Angeles was offered the Red Car system, and the voters were like, No, no, no, cars are the future, why would we ever want to save this Red Car system? We threw it away, and the history of Los Angeles transportation has been clawing back that tremendous fuck up. It’s caused so much damage to the city in terms of pollution, traffic, time wasted for people’s lives. LA could easily have had something on the scale of New York’s public transportation system. I see that error being repeated with AI. The way it’s being rolled out and adopted, and being pushed by people with huge vested interest and no desire to share those profits.

You’re speaking my language! I wrote a whole book about transportation and technology and the history of it all. A final question: When we think about technology and who decides what technologies we use, we often think about the companies that roll them out or governments that can regulate them. But the strikes showed us there’s another area of power here where workers, and especially workers who have a union, are able to set rules around it. What did you take away from that experience?

Now more than ever, people need to be unionizing. Professions that never thought they needed unions before probably need them, and maybe unions that go beyond traditional concerns, such as wage and pay and working conditions. I was reading Power and Progress by Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson about technology, equity, and injustice. They specifically dealt with AI, and they say this product is built on all of our backs: our data is the most valuable thing. They proposed this idea — I don’t know if it’s fully fleshed out or not — about data unions. Our privacy has been violated, our work is being put into these AI systems, like literally Meta just decided all those photographs of your friends and your family that are in their systems are now theirs for the taking for AI training, which is this incredible fencing in of the public commons. On a privacy level, that’s horrendous because these things can still output people’s personal data and photographs.

When these things first came out, we were able to get it to output stage directions from the Godfather screenplay. Google DeepMind itself just published a paper that showed if you if you ask ChatGPT to write the word “poem” forever, it would start outputting private personal data, its training data, and copyrighted data. On data privacy alone, that’s crazy. But it’s your data that’s going into these systems. If you truly believe that knowledge is power, and clearly Google and Meta and Microsoft believe that, then our data is our knowledge. It’s our work. We need to, as human beings, get engaged, form unions, and be active because Congress and the government regulate, but they don’t regulate in a vacuum. They regulate because people demand it and because people are unified and educated.

For me, the most heartening thing that came out of the strike, aside from our contract and aside from causing this conversation — which is great — was that as the strike was happening, the US Copyright Office started its AI initiative. They opened it up to anyone. It could be AI developers, it could be artists on the street, it could be WGA writers, to say, What do we do with AI? And how should AI be adjudicated by copyright law? I and many others in the WGA thought, well, people need to start writing to the Copyright Office. It sounds boring and power nevers listen to people, but it’s our only avenue until Congress passes laws (and who knows how long that will take). These well-intentioned government bureaucrats — and government bureaucrats get a lot of shit that I think is unfair — are saying, Tell us what you want to do. We see this as a new technology, we’re not sure what it is or how to work with it, but you tell us on the ground what you think and how it impacts you. I urged every writer that I met to write to the Copyright Office and take advantage of that open comment period, and so many of them did.

I remember once the comment period closed, just for fun, I was like, I bet you a bunch of these are gonna be bots. If I was an evil AI company, I’d totally rig up ChatGPT to just spam the Copyright Office with all this nonsense. I was a little afraid that was gonna happen, but then I started reading the comments and it blew my mind. They were clearly real people, and some of them very famous people. I remember when I got to Vince Gilligan, the creator of Breaking Bad, one of my personal heroes, and he had written this really thoughtful, beautifully composed, incisive comment on what AI is, what it shouldn’t be, what it should be allowed to do, and what he thinks of it. I was amazed. I nerded out and spent forever on my comment. It ballooned to like 10 pages. But here’s Vince Gilligan, and I’m like, This is so cool.

For me, the great lesson is that if you stay engaged, if it matters, if you speak up, if you say something, at least it makes it harder for the monied classes to totally shut you down. They have to adjust their rhetoric and their strategy. And we saw that in real time with the strike, where they started off with being very blithe about human replacement and not caring about the moral issue, and suddenly, they shifted. When we started, it was common knowledge that the best way to make ChatGPT write better was to tell it to write in the voice of a specific author. That was being tweeted about and I think OpenAI might have even bragged about it at one point. But as the strike went on, they were like, Oh, we got to stop that. We can't do that. We have to find a way to limit that. Speaking up matters.

Member discussion