I can hardly describe the dread that swept over me when I read the news that Netflix might end up buying Warner Bros. Discovery, and particularly the storied film studio at its core. The barbarians were not just at the gates, but had fully broken through the walls, reached the keep, and were nearly through the door to cast aside the king and seize his lands as their own. It didn’t seem as though an ally would arrive at the last moment to turn the tide of the battle, and the barbarians’ rule would be anything but a friendly one.

To some that might sound hyperbolic. I don’t think it is.

The prospect of Netflix acquiring one of the most recognizable US film studios feels not just like the culmination of the past nearly twenty years of Silicon Valley’s entry into and disruption of the film industry, but also a much longer process of the attempt to capture and commercialize culture — transforming it in the process to serve the ends of corporate tyrants rather than its essential function as a means of social enrichment. In that sense, Netflix is a problem because it’s both the product of a deeper rot in society and culture, while helping to extend its effects even further.

The false promise of streaming

For the past fifteen years, we’ve watched as the supposed “streaming wars” played out in front of our eyes. Tech companies moved into film and television, promising they could do it better than the old guard entertainment companies. Free to spend like drunken sailors, because investors valued them well above traditional companies and gave them free reign to lose money as they saw fit, they splashed out on prestige television and expensive auteur films to prove their bona fides, win some degree of industry support and acclaim, and get viewers on board with quality content and low prices — promising they would last forever.

But that was not to be the case. The streaming model upended the economics of film and television, drying up once-lucrative licensing revenue streams while further imperiling the collective theatrical experience in favor of the even further individualized viewing at home, which even shifted from the television to a laptop or phone screen. I’m guilty of watching in those ways too — well, not on a phone screen; I’ve never done that — but that doesn’t mean I think they’re the best ways of experiencing visual culture.

When I’m watching at home, I struggle to stay focused or to avoid my phone. But when I’m in a cinema, that completely changes. I’m there for the movie, my phone stays in my pocket once it starts, and I relish having that experience with a bunch of other people — even when it means I’m in tears multiple times, as was recently the case with Rental Family and Hamnet. Quite honestly, I dread missing a film like that in cinemas because I know the at-home experience just will not be the same. I enjoyed Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein immensely, but I was sad the theatrical run was so short and I missed the opportunity to see it on the big screen because I was traveling and busy with work.

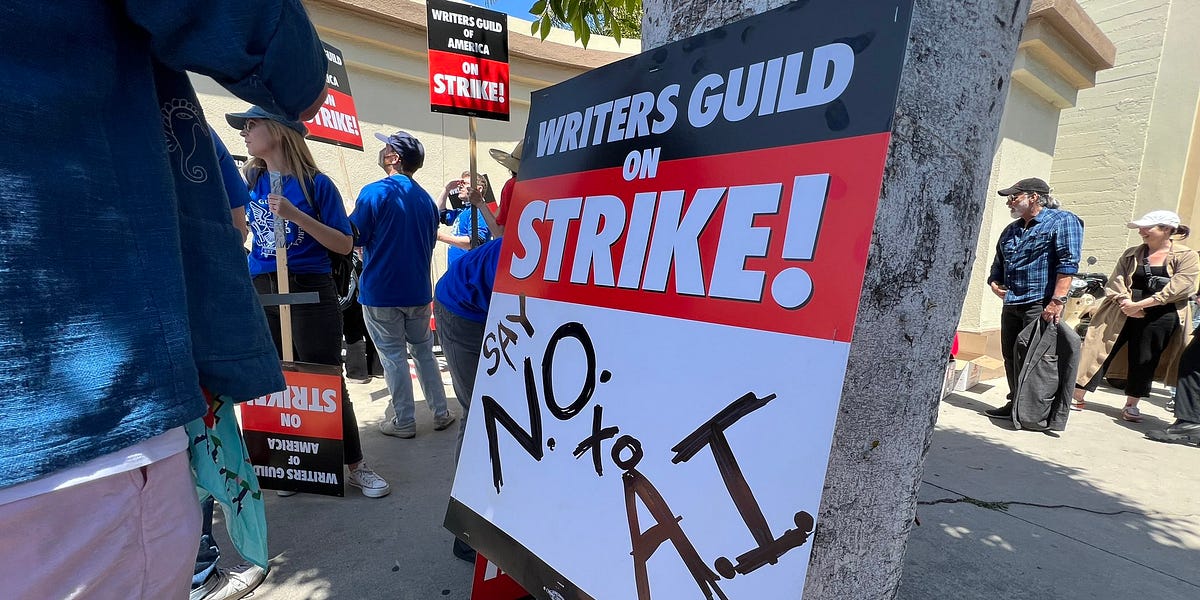

On top of all that, we’re now treated to a steady cadence of price hikes, not to mention crackdowns on once-popular password sharing, all while libraries get trimmed and the quality of the majority of content, especially on a platform like Netflix, is continually degraded to act as bottom-of-the-barrel background viewing with the expectation people are doomscrolling on another screen. It’s even leading the charge for Hollywood’s open embrace of generative AI, claiming it’s “all in” on using AI to cut production costs after deploying it for effects on a film for the first time earlier this year.

The false promises of the streaming revolution were entirely predictable to anyone paying attention to the business models of the companies behind it and the history of how these technological transformations tend to play out. In 1997, communications professor Thomas Streeter explained something very similar in the case of cable television. “The cable fable is a story of repeated utopian high hopes followed by repeated disappointments,” he wrote. “Cable was to end television oligopoly; instead it has merely provided an arena for the formation of a new oligopoly.”

Cable was supposed to bring about a more open and equitable media system, but ended up reinforcing corporate power in the sector. Streaming may have brought in some new players, but it ended up doing much the same — while creating the pressure for even further consolidation as massive, well-financed tech firms moved in as competitors.

Disney gobbled up most of 21st Century Fox in its effort to scale up, AT&T (including WarnerMedia) merged with Discovery, Amazon absorbed MGM Studios, the Ellisons grabbed Paramount, a bunch of smaller companies have been scooped up too, and now the vultures are circling around the combined WBD for another scale up. None of this enriches the culture; but investors do hope it will allow them to extract some gains after further cost-cutting measures.

Streaming has eroded the business model that funded culture for decades, leaving companies scrambling to find out how to make the numbers work in this new era. There seems to only be room for a few massive platforms and maybe a few niches ones besides them, but the notion that the model would foment better culture, more opportunity, and increased competition has long ago been disproven. Even before the pandemic, creators were already calling out opaque decision-making at Netflix and how it was disproportionately cancelling series made by women.

It didn’t start with Netflix

While it’s easy to put all the blame on Netflix, and it certainly doesn’t deserve to be let off the hook, the corporate effort to commercialize (and in the process degrade) culture did not start with streaming. As Streeter’s decades-old observation suggests, this has been going on for a long time — and new technology has been a key part of the game. It’s played out in many different ways.

In the 1970s, the blockbuster movie changed the nature of going to the movies and used spectacle to encourage consolidation of independent cinemas into multiplexes, giving owners leverage over unionized projectionists in the process. But as Will Tavlin explained in a fantastic piece in n+1, the distributors came for those cinema owners a few decades later. When movie projection shifted from film to digital cameras in the early 2000s, the companies set a new standard that “made sure that as distributors they would maintain their leverage over exhibitors” — even as the cost and difficulty of servicing the new projectors led to a decrease in the quality of the moviegoing experience. As the studios gained more power, they also started pushing more onerous terms on cinemas too and restricted access to catalogs of older films.

Today, the roles have shifted. Studios have not been defanged — a company like Disney can still have a lot of leverage — but ownership of a major streaming platform comes with a lot of leverage. Netflix has basically snubbed cinemas that don’t want to give into its demands of incredibly short theatrical windows and doesn’t license out its originals. It wants to extend its control as far as possible and has effectively used technology (and deep pockets) to do just that. In a sense, the effort to shoehorn generative AI into development isn’t just a cost-cutting measure; it’s also an attempt to seize more power over the production process. If you can easily generate a new scene or alterations to an existing one, that takes power away from writers, actors, and even directors.

There is precedent for this. When computer-generated effects were maturing and being popularized in the 1980s, there were promises about the new filmmaking techniques it would enable but also concerns about the power that was being shifted to directors in the process. In her book The Empire of Effects, Julie Turnock explains that the role of George Lucas and Industrial Light & Magic in advancing visual effects is often overstated. Lucas was “willing to invest significant funds to develop technology to make editing, sound, and special effects easier and less expensive,” but he “squandered nearly every opportunity” with the dream team he’d assembled because he was more focused on transforming the way films were made to give himself more power over the final product.

When it was time for Lucas to shoot the Star Wars prequel trilogy, the technology had advanced far enough to give him an unprecedented degree of control over the look of the films — regardless of whether he’d been able to capture what he wanted in camera. “In postproduction for The Phantom Menace, performers were copied from some shots and pasted into others; actors who blinked on a cut were made to keep their eyes open; cast members who turned their head to Lucas’s disliking were turned the other way,” explained Tavlin. Lucas’ editor said essentially that. “We could totally redirect the picture in the cutting room.”

Despite all the claims of technological efficiency, budgets have not shrunk — in fact, they’ve only gotten larger. The claims of cost savings did not materialize, but the unacknowledged seizure of control certainly did. That’s something to keep in mind as similar arguments are made about generative AI. Actors and writers have already shown concern about how new technology has eroded their leverage in film production. “After their work is done, those offshored VFX companies do a lot of the rest of the ‘writing’, just as they now do a lot of the rest of the ‘acting’ once the stars have gone home,” wrote A.S. Hamrah of the way things have changed with visual effects and digital production. That’s only poised to get worse if companies get their way with image and video generators.

Where we go next

The prospect of further consolidation, especially an acquisition by a company like Netflix, should be cause for alarm well beyond the communities of those who actually make film and television. We’ve already seen a form of content slop emerge from the streaming era, as the focus has become on churning out enough programming to keep people engaged — quality be damned, because the viewers are assumed to be on their phones most of the time anyway. Going further down that path, with the addition of generative AI as another tool to wield against creators to further remake art to serve commercial ends is the wrong path.

That’s not to let Paramount and the Ellisons off the hook. While Paramount itself may at least have industry pedigree, the project David Ellison is trying to manifest with the backing of his father, who just happens to be the richest man in the world every now and then, is to remake one of the old guard film companies — or a few, if WBD can be rolled into the project — into the mold of a modern tech company to take on the tech interlopers like Netflix. We also shouldn’t ignore the power that would come with such an empire, spanning film, television, video games, and potentially even social media if the deal for the US arm of TikTok ever comes to pass, nor the mass layoffs and consequences for film and television production that would follow from the merger of two major studios.

We’ve even seen the consequences of this through existing mergers: there’s been far less out of Fox after it was taken over by Disney, which itself just got into bed with OpenAI in a short-term bid to cash in on the generative AI boom regardless of the wider consequences. In a sense, Silicon Valley isn’t even the cause of these problems. At its core, this is a capitalist problem as the system needs to absorb and remake every facet of society in an attempt to extract profits at all costs. The tech industry is simply the driving vehicle of that process in the current moment, which is why it deserves so much attention — and opposition.

At the end of the day, WBD should not merge or be acquired by any company. Regulators should stop any such effort at further consolidation in its tracks and make it clear this has to stop. But it should also go back to the earlier days when more strictly regulating these companies to limit their size and their power was much more in vogue — and expand that to the tech companies and their streaming revolution. Technology itself isn’t even the problem — it’s the pressures of the economic system we live in to create technology whose goal is exploitation and commercialization, not cultural enrichment and human flourishing.

More than anything, culture needs to be seen as the public good that it is — and proper funding given over to ensure it can flourish and enrich our lives, even when it doesn’t present the prospect of corporate profits. That’s not a project Netflix — or any of these corporate behemoths — will be an ally to achieve.

Member discussion