On September 9, Apple held its annual keynote presentation to announce its new slate of iPhones. There weren’t any big surprises in the announcements, as has become common at these events. The phones get a little faster, the colors change a little bit, the camera gets an upgrade, and they give another preview of software upgrades, which this year includes Apple Intelligence — Apple’s attempt to ride the wave of AI hype but which is being met with underwhelming reviews.

The keynote could be summed up as little more than a marketing stunt to convince people they need a new metal brick in their pocket that isn’t very different from the old metal brick already occupying that space. Yet, every year, there seems to be a chorus of indignation that there isn’t more to see from these devices, with some even going so far as to blame tech monopolization for a lack of smartphone innovation.

There’s no doubt the smartphone market is an oligopoly — on the software and hardware side — and that Apple wields an immense amount over power over the software ecosystem on its devices, but sometimes monopolization gets blamed for things it’s not actually responsible for, and I would argue this is one of those times. The reality is that the smartphone is done. From here on out, it’s only going to get incremental improvements and occasionally gimmicky features, and that’s fine.

Experimentation still happens

Seventeen years since the original iPhone, it can be hard to put in perspective how significantly the smartphone changed not just how we communicate, but so many other aspects of our lives. Increasingly many of the services we rely on have become linked to smartphones in some way or another, if not requiring them for their use. We often talk about wanting to reduce our smartphone reliance, but it feels almost impossible to go back to a pre-smartphone era, before the internet was in our pockets and connectivity was constant.

For about the first decade, as companies like Apple, Google, and Samsung were figuring out the basics of the smartphone experience and improving the tech that went into them, it felt like there were more significant leaps in their capabilities, occasional new hardware features that justified more frequent upgrades, and especially longer battery life that people craved. But the days of those more notable improvements are long gone.

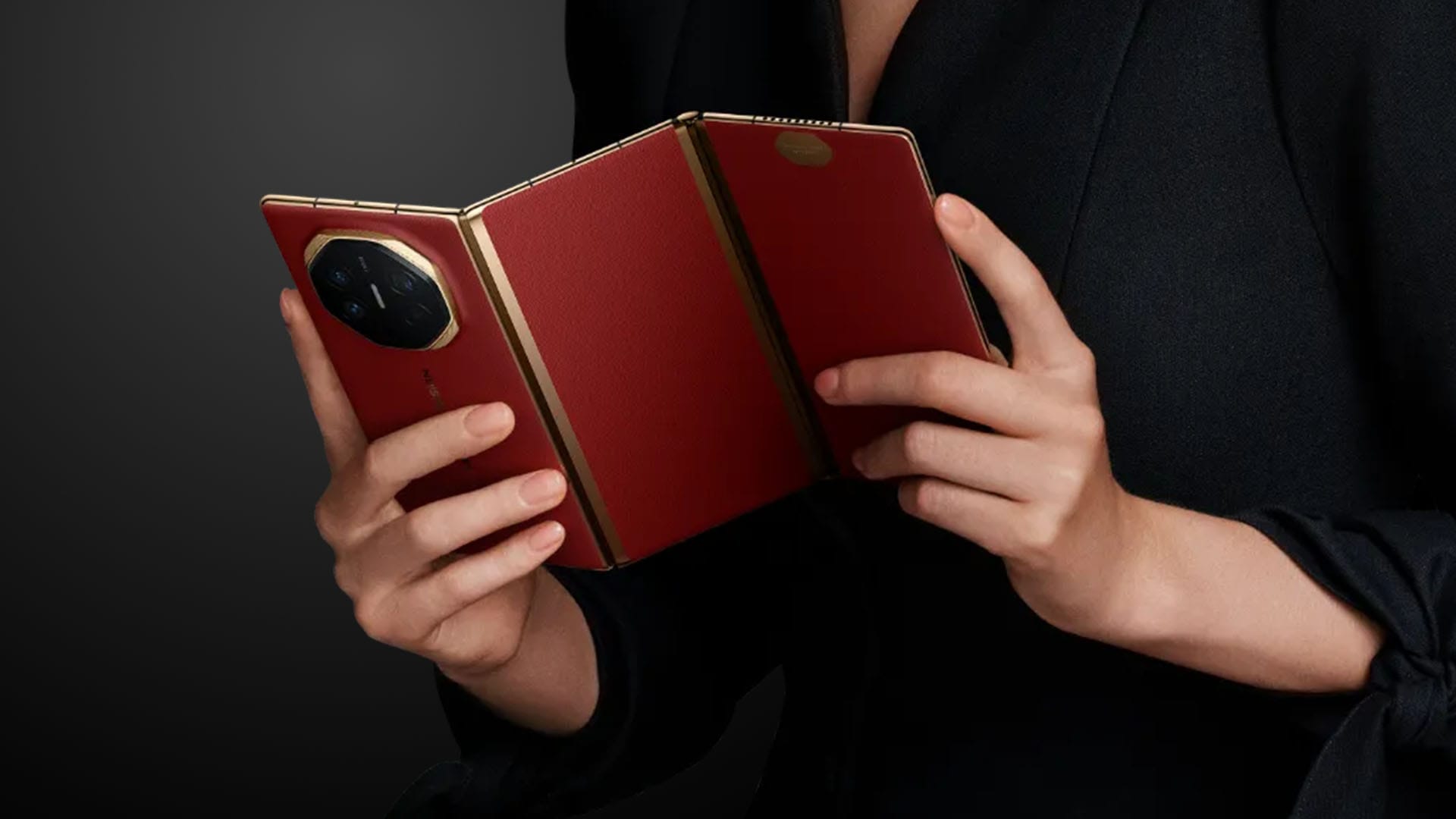

These days, the annual iPhone upgrade cycle is not about rolling out new industry-upending features, but about trying to entice more sales, keep investors happy, and continue the trend they’ve set since the iPhone 5 of a new smartphone every September. Other manufacturers do something similar, they just don’t get as much attention for it because they’re not Apple, and as a result, they tend to offer more models and try out new features because they need to catch the attention of consumers and the press. Experiments like folding screens aren’t about transforming the smartphone; they’re gimmicks to try to entice some purchases.

Mere hours after Apple’s keynote, its Chinese competitor Huawei held an event of its own in Shenzhen and showed exactly how this works. The company set the date and time to try to position itself against the iPhone and showed off the first ever smartphone with two folds, costing $2,800 or 19,999 yuan. It’s great to see Huawei experimenting on the hardware side, but it certainly doesn’t expect the Mate XT to sell like an iPhone or even its more mass-market phones (that do sell incredibly well). It was a play for press attention, which it surely received in China, but not nearly to the same degree in Western countries.

Huawei’s press conference shows there is still experimentation happening in the smartphone arena, but the core of the smartphone experience is not going to significantly change with the things Samsung, Huawei, or other manufacturers experiment with to entice consumers. That’s why I call them gimmicks — they can be interesting and add something unique to a marketing pitch, but that’s all they are. A point of differentiation from the 800-pound gorilla that dances to its own tune.

The smartphone model is set

At a certain point, every technology reaches a point where its advancement slows down, if not stalls outright. We don’t expect our refrigerators to significantly change every few years, and our cars and laptops have been in that incremental stage for a long time. The shift to electric motors or ARM processors brought some changes and improvements to the core product, but they don’t fundamentally change what a car or a laptop is at the end of the day. Smartphones reached that stage years ago, but for some reason there’s a vocal group of people who don’t want to accept it.

Apple deserves our ire, as do many of the other companies that share its oligopolistic dominance over the smartphone market. But a lack of competition isn’t what’s stalling smartphone innovation. There are plenty of gimmicky features to choose from in the Android market and smaller companies are making more ethical, modular, and distraction-free alternatives for the niche groups of people who want them. The divide appears to be a common one in tech: that a small group of people who are interested in those niche products want the mass market to adopt them, even when they themselves might also be using the mass-market products.

Most people just want a phone that’s going to work, not something that’s unnecessarily complicated. Now that smartphones are more of a commodity than a cutting-edge product, people will hold on to their phone until it breaks then get a new one that does the things they need it to do. There’s absolutely nothing wrong with that and taking on the smartphone oligopoly won’t change it.

Member discussion