Since late last year, generative AI has been all the rage — and no product has received more attention than ChatGPT. After its release, it quickly racked up more than 100 million monthly users as the media obsessed over transcripts of journalists’ conversations with the chatbot as though it was really engaging with them and the industry promised this was just the beginning: generative AI was going to upend society — and potentially even threaten the future of humanity.

But ever since the beginning of the hype cycle, there’s been ample reason for skepticism of the narratives being deployed by OpenAI and the other companies and executives incentivized to make chatbots and image generators out to be the next big thing. Was it really any surprise that a free tool got a lot of users to give it a shot when virtually every news program couldn’t shut up about it? And were the expansive claims the industry was making ever an accurate reflection of the reality of the technology?

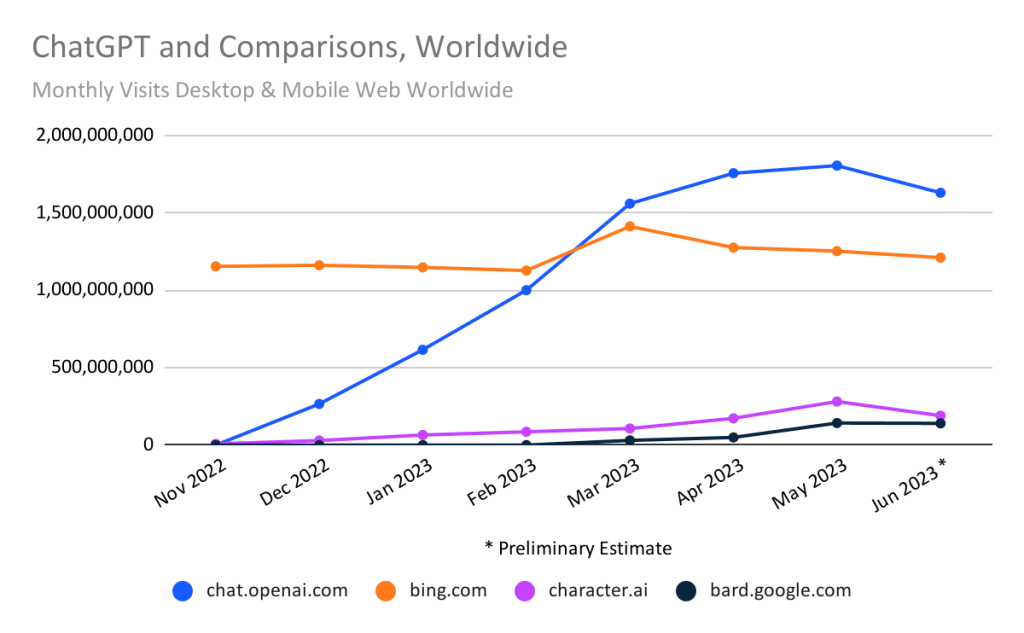

Earlier this month, data from SimilarWeb — the same company whose figures were used to tout ChatGPT’s rapid user growth earlier this year — showed that just over six months since its launch, ChatGPT saw its worldwide traffic fall 9.7% in June, while unique users dropped 5.7%. Some defenders of generative AI explained the decline by pointing to students getting out of school and not using it for their essays any longer, but SimilarWeb’s data shows the service’s rapid growth began to stall out back in March, well before its June decline.

Even if we can explain the drop in traffic by changes in student usage — something I’m not convinced by — it still doesn’t bode well for such a new product that’s supposedly only beginning to transform how we live, work, and engage with digital services. I would argue that statistic points to the fragile foundation the generative AI hype has been built on, and how its reputation is much more hot air than real promise.

The next big thing

When generative AI emerged onto the scene at the end of 2022, Silicon Valley was in a rough place. After building an operating model on the assumption of low interest rates, central banks were rapidly hiking them for the first time in over a decade, squeezing off easy access to capital and demolishing the entire idea of how a tech company should lose boatloads of money to achieve rapid growth. Meanwhile, the industry’s last big bets had also collapsed.

The crypto hype peaked in November 2021, then experienced a series of crashes and bankruptcies through 2022, and the metaverse didn’t fare much better. After a ton of companies jumped on Meta’s bandwagon, they just as quickly abandoned their experiments as it became clear the public saw Mark Zuckerberg’s virtual fantasy as more of a joke than a bright future. But those challenges left the industry in a difficult position. Growth was slowing, the pandemic boom experienced by major tech companies was over, large layoffs were being made across the industry, and there was no next big thing.

Silicon Valley relies on a boom and bust cycle to survive. Malcolm Harris, author of Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World, describes how Silicon Valley’s takeaway from the dot-com crash at the turn of the millennium wasn’t to avoid another bust at all costs, but to keep creating new bubbles they could profit from until their collapse, then begin the cycle anew. After crypto and the metaverse, it wasn’t clear what would fill the void — but something was needed to shore up an industry in the sort of rut it hadn’t seen in years. Investors were awaiting a new idea to drive another wave of investment, then ChatGPT exploded onto the scene.

Repeating the playbook

Generative AI followed the typical model of a tech hype cycle. One minute, few people had ever heard of the product, let alone used it. Then, all of a sudden it was everywhere and we were bombarded with stories about its magical qualities and unparalleled capabilities alongside warnings about what it could mean for jobs, society, and the future of our entire species. It was no wonder people were curious and even worried, especially when they didn’t have the skills to assess the tech’s potential for themselves. But it was also very similar to how other tech products have exploded onto the scene in the past, only to be largely forgotten a few years later.

For me, the generative AI cycle contains eery parallels with the last time AI and automation were supposed to upend society. Maybe you remember, because it was about a decade ago. At that time, the industry and its media mouthpieces were breathlessly telling us about how the robots were on the cusp of taking many of our jobs. Truck and taxi drivers were about to be eradicated by self-driving cars, baristas and food service workers were going to be replaced by robotic arms, AI bots would take the place of artists and journalists, and robots would proliferate into many other areas of the economy.

That led to a certain degree of panic as people wondered what our society would look like once those predictions came to pass, something that was sure to be felt in the very near future. Would we need a basic income to ensure people didn’t starve? Was it the first step to fully automated luxury communism? Or would we all simply become immiserated as the billionaires of Silicon Valley reaped even more of the gains in an already vastly unequal economy?

But the reality looked far different from the industry’s big predictions because the automation boom didn’t really happen. Aaron Benanav, author of Automation and the Future of Work, explains that “productivity growth rates in manufacturing collapsed precisely when, according to automation theorists, they were supposed to be rising rapidly due to advancing technologies.” Instead, the threat of automation was used as a distraction from a more serious development. Tech companies, followed by other employers, used the post-recession moment to roll out a bunch of new digital technologies designed to disempower and deskill labor.

Using tech against workers

The most obvious example of that phenomenon is the gig economy, where companies like Uber and the many imitators it inspired used the excuse of app-based service mediation to argue that workers were no longer employees, but contractors, denying them the many labor rights that come with employment status. Amazon did something similar. The ecommerce giant rolled out algorithmic management through its warehouses and later delivery network to ensure workers were constantly tracked and subjected to high production targets that leave them at greater risk of injury and needing to pee in bottles because they can’t take a break to go to the bathroom. But it also took professions like logistics and delivery that are traditionally unionized, and fought to turn them into non-union jobs with much lower salary expectations.

Even where those algorithmic tools were deployed, they weren’t simply replacing humans workers with computers; what happened was much more complex. All of those systems relied on a lot of poorly paid labor in places like Africa and Asia, who were either hired as contract workers through third-party companies or sourced through clickwork platforms like Amazon’s Mechanical Turk to do small tasks for mere pennies. Companies are effective at hiding that labor from us, making it look like the computers are doing everything on their own, and that continues with generative AI.

In January, two months into the ChatGPT hype, Time published an investigation into some of the human workers that helped train the chatbot. Reporter Billy Perrigo found that contract workers in Kenya had been paid less than $2 an hour to read incredibly toxic and emotionally traumatizing content documenting things like child sexual abuse, torture, and self harm to avoid having OpenAI’s chatbot respond to such prompts or spit it out in an answer. More recently, the Wall Street Journal went back to speak to some of those workers. They described how the experience left them with social anxieties and harmed their relationships, and they weren’t given the proper mental health supports once the company was done with them.

These generative AI tools were made possible by indiscriminately scraping the open web to take whatever the companies wanted to train their models. The tech hasn’t notably improved; they’re just using a lot more data and even greater computing power, which allows them to get slightly better results than in the past. They stole the work of artists, writers, and photographers, regardless of its copyright status, and some now argue we should accept that abuse of their rights as fair use. It also meant they took a ton of photos and posts made by regular people, and are facing a lawsuit over the theft of private data. But processing all that data also has a huge material footprint.

A growing environmental toll

Just as the labor behind AI is hidden by the way the systems are constructed, so too is the resource burden necessary to make chatbots and image generators possible. These massive AI models require tens of thousands of graphics cards and those components, along with all the others needed to run the models, require extensive mining for the minerals that go into them. While the AI tools seem to just work when a consumer goes to use them, there’s a massive computing infrastructure of hyperscale data centers positioned around the world making that possible — and that infrastructure isn’t without controversy.

Chatbots and image generators require more computing power than many of the tasks we’re used to doing online that they’re supposed to replace. Conversing with a chatbot, for example, is estimated to have a carbon footprint four to five times greater than using a search engine to get an answer, and that means more energy is required and it’s much more expensive. While the industry has made a lot of promises about moving to renewables, a lot of that energy is still derived from fossil fuels, and as Alan Woodward, a professor of cybersecurity at the University of Surrey told Wired UK, “Every time we see a step change in online processing, we see significant increases in the power and cooling resources required by large processing centers.”

That’s the other thing. Those data centers don’t just require energy, they require water, and right now they’re usually built in places where energy is cheap, but those sites also tend to be areas where water is scarce, exacerbating existing shortages. For example, the training of GPT-3 was estimated to require 700,000 liters of freshwater in Microsoft’s data centers, while a short conversation with ChatGPT could use the equivalent of a 500-milliliter bottle of water — which might not seem like a lot, until you consider the millions of daily users and the corporate goal to massively expand it. Plus, academics told The Markup that number is just for operational use; the water footprint of the entire production process, including server manufacturing and transportation, would be ten times greater, if not more.

Companies have been trying to hide the full footprint of their data centers because they know the public could turn against them if they knew the reality. In The Dalles, Oregon, Google was found to be using a quarter of the city’s water supply to cool its facilities. Tech companies have been facing pushback elsewhere in the United States, but also across the world in places like Uruguay, Chile, the Netherlands, Ireland, and New Zealand. Now opposition is growing in Spain too, where droughts are wiping out crops and people are wondering why they’d give their limited water resources to Meta for a data center. But adopting generative AI will require a lot more of those data centers to be built around the world.

The tech industry is constantly incentivized to increase the computing power we use as a society, because that works for their business models — especially when Amazon, Microsoft, and Google have massive cloud computing divisions. But we never seem to stop and ask whether that additional computing power is necessary to improve our lives. As Hugging Face climate lead Sasha Luccioni told The Guardian, “we’re seeing this shift of people using generative AI models just because they feel like they should, without sustainability being taken into account.” Everyone’s jumping on the bandwagon, but it’s not clear that’s actually in anyone’s interests but those of founders and investors who are hoping to cash in on the latest AI bubble.

Don’t buy the hype

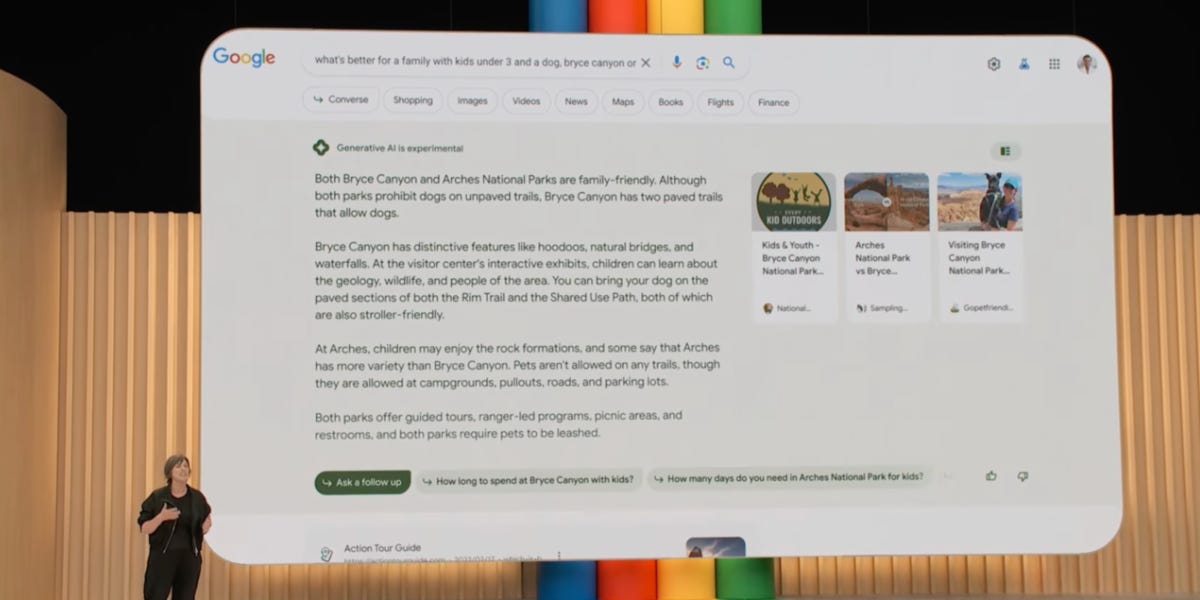

Despite all the hype, it’s becoming increasingly clear that we’ve been oversold on the transformation generative AI is going to deliver. The big initial narrative was that it was going to transform search, and specifically allow Microsoft’s Bing to take market share from Google as it integrated OpenAI’s tools into its search engine. Well, that didn’t happen. If anything, Google’s market share has slightly increased.

The image generators are still plagued with problems of their own because not only are they not intelligent, but they can’t actually create anything new. They’re just remixing versions of the images that the models have been trained on, and it will be bad news for our culture if we let AI shape the future of human creativity. Even the chatbots that have had the most hype aren’t keeping up. Regular users of ChatGPT have been reporting the tool has actually been getting worse over time, and new research seems to back that up.

Again, that doesn’t mean it won’t have any impact, but it won’t be nearly as transformative as the CEOs, investors, and general tech boosters want us to believe; the myth of its inevitability and broad applicability will simply be used against workers, especially at a moment when they have an unusually high degree of power to make demands from their employers. AI will be one of the weapons used to crush that power. And as Dan McQuillan has warned, those AI tools can be used in much more dangerous ways to shape how the rest of us live, whether it’s to deny people welfare benefits, increase the policing they’re subjected to, or build discrimination into important systems like visas and immigration.

But the people in charge of these companies don’t tend to care about that. Instead, they’re working hard to distract us from the environmental, labor, and social concerns with fantasies about AI’s potential threat to the human race as a whole. It’s part of a broader longtermist ideology that seeks to shift our resources from present-day crises to the priorities of fabulously wealthy and hopelessly disconnected tech billionaires. Executives like OpenAI’s Sam Altman have been praised for welcoming regulation, but his real goal in going on a world tour to speak to political leaders was to shape those regulations so they work for his company — just as Time reported he did in the European Union.

Once again, the tech industry has deceived us in another bid to expand their power and increase their wealth, and much of the media was all too happy to go along for the ride. Generative AI is not going to bring about a wonderfully utopian future — or the end of humanity. But it will be used to make our lives more difficult and further erode our ability to fight for anything better. We need to stop buying into Silicon Valley fantasies that never arrive, and wisen up to the con before it’s too late.

Member discussion