How Hollywood used the digital transition against workers

The challenge facing striking workers goes much deeper than streaming and AI

On May 2, Hollywood writers went on strike for the first time in 15 years. More than a decade into the shift to streaming, the new business model of the industry isn’t fairly compensating the workers responsible for the film and television that captivates people the world over. Two years ago, it was the craftspeople, cinematographers, and other below-the-line workers represented by IATSE that nearly went on strike over the conditions they’re subjected to under this new model, while visual effects artists and animations workers have also been speaking out and organizing in recent years too.

Many of the major entertainment and streaming companies are still pulling in big profits despite claiming poverty. Over the past couple decades, they’ve been merging into even larger conglomerates, especially when they needed to compete with much better capitalized tech competitors. Disney gobbled up Marvel and Lucasfilm, then captured 21st Century Fox, one of its major competitors. Amazon now owns MGM Studios, while Discovery has taken over Warner Brothers. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

What’s happened here is twofold: Companies are merging, which gives them even greater leverage against workers, but also any smaller companies that depend on them for business (like cinemas). Plus, they’re developing and rolling out new technologies that restructure the conditions of the industry to further enhance their power.

This has been going on since the very early days of the industry. While there had been writer organizing since the 1910s, it wasn’t until after the introduction of the talkies in 1927 combined with the beginning of the Great Depression in 1929 that renewed energy was put into the Screen Writers’ Guild in 1933, eventually resulting in the first Minimum Basic Agreement for writers in 1941. It’s that Basic Agreement that the Writer’s Guild of America was in the process of renegotiating before writers went on strike.

The story of today’s problems usually revolves around streaming, and Netflix in particular. It launched its streaming service in 2007, and released House of Cards in 2013, really kicking off the race for other companies to compete, consolidate, and carve out a slice of the streaming pie for themselves. Not to let Netflix off the hook, but the problem runs much deeper than streaming and all the major studios — not just the tech companies — are implicated.

The digital transformation of the film industry has been a decades-long process not just to switch to a new set of technologies, but also to further shift the power over film and television production into the hands of those at the top of the major studios, and now the tech companies who’ve moved in too. The process isn’t over, and to be able to push back on it, we also need to understand how it happened.

Studios squeezing cinemas

The film industry is typically divided into three broad categories: production, which is the process of actually making film and television; distribution, which involves making deals to get it to audiences; and exhibition, which is when it’s shown to audiences. That latter stage typically refers to movie theaters. Today, the major studios are typically involved in production and distribution — they make movies and ensure people watch them — but before 1948, they also owned cinemas of their own.

During that period, the industry was set up almost like a factory, with a steady stream of films going out to their cinemas and sold to independent theaters. But the studios also had immense power, giving them a lot of leverage over independent theater owners to make them take their entire slate — to get the good movies, they also had to show the bad ones. It was a process called block booking, and in 1948 the US Department of Justice won a case against the major studios arguing they’d abused their market power. As a result, they had to abide by the Paramount Consent Decrees, which forced them to sell off their cinema chains and regulated the deals they made to distribute their films to theaters.

In an article for n+1, Will Tavlin explains that the blockbuster emerged in the 1970s, beginning with Steven Spielberg’s Jaws, as a response to this problem. Instead of making a ton of smaller films, the major studios would make fewer but the ones they did make would be bigger, and because people felt the need to see them as soon as they came out, the studios would get a bigger cut of the ticket sales. This new model encouraged the shift away from small independent cinemas toward large multiplex chains as people rushed in to see the blockbusters, and that gave cinema owners leverage over workers: with so many screens showing the same film, they didn’t need as many unionized projectionists. Instead, they could tape the film’s reels together and use automated platters to play it on multiple screens at once. But Tavlin explains that also had consequences for the viewing experience.

The projectionists who screened [blockbusters] found their hours scaled back and their jobs more difficult. At the largest multiplexes, projectionists were sometimes forced to monitor more than twenty screens at once. Projection quality suffered. Misaligned projectors, out-of-focus images, and deafening or muted sound levels became the multiplex norm. Interlocked film prints were rigged between walls, sometimes into lobbies and over popcorn machines, and were exposed to more harm. A single misaligned roller could engrave an emulsion scratch across an entire print. A misthreaded film could bunch up in the platter and melt.

Decades ago, even before the shift to digital, you can see how the experience of going to the movies was already being degraded in service of the profit motive: getting bigger movies on more screens to get a rapid influx of cash, and disempowering labor in the process. The next stage of this occurred in the early 2000s when the pressure to go digital had reached a fever pitch.

Seeing how things were going, the major studios got together in 2002 to form Digital Cinema Initiatives to set the standard for digital projection in a way which “made sure that as distributors they would maintain their leverage over exhibitors,” writes Tavlin. The new standard, called the Digital Cinema Package, not only continued the attack on projectionists, but by shifting to digital files distributed by the studios, theaters were completely at their whim. They had to switch from film projectors to digital projectors at a cost of $50,000 to $100,000 per screen, Tavlin explains, and they required much more maintenance: up to $10,000 per year, compared to $1,000 to $2,000 for film projectors. It took less than a decade for studios like Fox and Paramount to stop offering their back catalog on film.

Just over a decade ago, when Avatar spurred cinemas to accelerate the transition, AMC went with Sony projectors, but digital projectors are estimated to only last about ten years. In 2020, Sony announced it was getting out of the business of making them, leaving fewer options, and it recently stopped servicing those still in use. That shift to digital and its associated high costs for cinemas, along with the sidelining of skilled projectionists, has had an impact on the experience, like when multiplexes were interlocking their film projectors. Films have adopted a darker aesthetic over the past couple decades, but films can look much darker for many other reasons: 3D filters that aren’t removed when showing 2D films, imaging devices (particularly in those Sony projectors) that haven’t been replaced, or even light bulbs that haven’t been replaced as they’ve become less bright to cut costs.

This is the aspect of the digital transition that’s most hidden from view, but it shows how the major studios took charge of the process and ensured it served their interests. Sure, theaters owners also got some benefits as they shrugged off their projectionists, but ultimately the studios got the majority of the gains. Otherwise, it’s unlikely studios like Disney would’ve been able to start pushing onerous terms on cinemas to show their biggest blockbusters before the pandemic, demanding a larger cut of ticket sales and making it mandatory to show the movies on their biggest screens for four weeks after release. But the shift to digital has also shifted power up the chain of command on the production side too.

The digital power grab

George Lucas was one of the big filmmakers behind the move to blockbusters with his involvement in franchises like Star Wars and Indiana Jones, and made a huge contribution to moving forward the digitization of film production. He founded Industrial Light & Magic (ILM), which not only did a lot of physical special effects work, but also became a key player in the move toward computer-generated imagery, or visual effects. But in The Empire of Effects: Industrial Light and Magic and the Rendering of Realism, Julie Turnock explains that ILM’s contributions to early work on visual effects in the 1980s is often overstated.

Lucasfilm, separate from ILM, had a Graphics Group doing groundbreaking work in the 1980s, but “Lucas (as well as ILM on the Lucasfilm production side) squandered nearly every opportunity with this computer graphics dream team,” writes Turnock. Lucas was much more interested in altering the production process, and was “willing to invest significant funds to develop technology to make editing, sound, and special effects easier and less expensive.” He wanted the Graphics Group to create a film-to-computer-to-film scanning device that would become the Pixar, and had other projects working on non-linear editing and digital sound. Lucasfilm even sold the Graphics Group in 1986 to Steve Jobs, becoming the Pixar computer animation studio, and Turnock argues corporate histories overstate how much Lucasfilm set the foundation for the division’s later success as an independent entity.

The effect of those investments is clear by the late 1990s when Lucas made his Star Wars prequel trilogy. The second film in that trilogy, Attack of the Clones, was the first Hollywood feature film shot entirely on a digital camera, and the digital editing process paired with advances in computer graphics gave Lucas an unprecedented degree of control over the final product of the three films. As Tavlin explains,

Digital gave Lucas total command of the frame, allowing him to wholly rework his vast quantities of footage in the editing room. In postproduction for The Phantom Menace, performers were copied from some shots and pasted into others; actors who blinked on a cut were made to keep their eyes open; cast members who turned their head to Lucas’s disliking were turned the other way. Lucas’s editor claimed that there wasn’t a single shot in the film that he and the director hadn’t manipulated. “We could totally redirect the picture in the cutting room,” he explained.

Even though the move to digital was cast as a democratizing force, this example shows the true motivation behind its development: to take power away from performers and the workers on set, shifting it toward the director and even the suits who have growing influence over the final cut of films in major franchises. Tavlin shows how the cost savings didn’t materialize on the Hollywood level, as budgets continued to expand as directors captured more footage, expected a lot more visual effects, and had to pay much more to store all that digital footage than they did with film. But it did ensure greater control over production, especially when combined with the trend toward blockbuster franchises based off popular intellectual property.

Digital production ensured virtually anything about a film could be changed in post-production. Keanu Reeves has discussed how he has a clause in his contracts ensuring his performances can’t be digitally altered without his approval because it happened to him on previous film, saying you “lose your agency” with technologies that enable it. He’s big enough to make such a demand, but not everyone is.

The shift to this model of production also has an effect on writers. “In the age of IP, the writing has already happened,” explains writer A.S. Hamrah.

The post-IP writer, under this system, becomes the equivalent of a machine with a semi-consciousness, because so much of the work of writing has already been done. … And after their work is done, those offshored VFX companies do a lot of the rest of the “writing,” just as they now do a lot of the rest of the “acting” once the stars have gone home.

But that doesn’t mean the power taken from many actors, writers, and craftspeople accrues to visual effects workers, who don’t have a union or collective agreement.

Visual effects work is increasingly outsourced to places like Southeast Asia, but even when it isn’t, studios like Marvel have pioneered a production model where work on a single film gets broken up among among multiple visual effects houses — major films like The Avengers have used more than twenty — to ensure the power remains in Marvel’s hands and the visual effects companies have little leverage. If they do push back, they can be blacklisted from future work. Because of the pressure Marvel and other studios place on effects companies, workers are subject to stress and long hours, and the pressure of short deadlines ultimately impacts the quality of the work. As a visual effects artist told Vulture’s Chris Lee,

A good example of what happens in these scenarios is the battle scene at the end of Black Panther. The physics are completely off. Suddenly, the characters are jumping around, doing all these crazy moves like action figures in space. Suddenly, the camera is doing these motions that haven’t happened in the rest of the movie. It all looks a bit cartoony. It has broken the visual language of the film.

The Marvel production model results in a “moviemaking-by-corporate-committee production process,” explains Turnock, “where every film and every moment is massaged or ‘plussed’ for maximum appeal” — shifting power away from even directors like Lucas. For Tavlin, the takeaway from this process is clear: “Hollywood executives prefer the high costs of a film that is reshaped in post, that has 5,000 percent more footage, for a simple reason: digital filmmaking offers more opportunities for studio executives to control the picture after it’s been shot.”

The false promise of streaming

One aspect of this digital transition we haven’t discussed is streaming. Remember what I said earlier, that the film industry is divided into production, distribution, and exhibition. On the film side, studios have been effectively restricted from owning cinemas since 1948 — or they were, until the Paramount Decrees were repealed in 2020, with streaming deceptively presented as a means of enabling additional competition that made them unnecessary. There were also restrictions on how much of their own programming broadcast networks could air before the 1990s.

But in the same way blockbusters allowed studios to get around some of the restrictions in the Decrees by changing the types of films they produced, streaming allowed them to get around the restriction on exhibition. Streaming services are essentially exhibition platforms; they allow the studios to go direct to audiences and gain control over that section of the industry as well. Instead of streaming services and content production being separate, a platform’s original content is often a key selling point. While content was in high demand, that meant studios or production companies without their own services weren’t disadvantaged, but as content budgets become constrained that could seriously change.

We’ve already seen how streaming has changed the game, and allowed the companies that control the major services to have even more power over the industry. Transparent streaming audience data is hard to come by, yet it’s easy to get box office figures and television viewership numbers. Services like Netflix are known to base content decisions off opaque metrics and algorithms, and will quickly cancel shows if they don’t generate enough subscriptions. While streaming was presented as democratization and a paradise for creators, that’s significantly changed in recent years as they’ve preferred mass-market and lower cost content. Now they’re hiking prices, taking content out of their libraries, and adding more advertising — breaking promises they once made to consumers.

AI is the next step

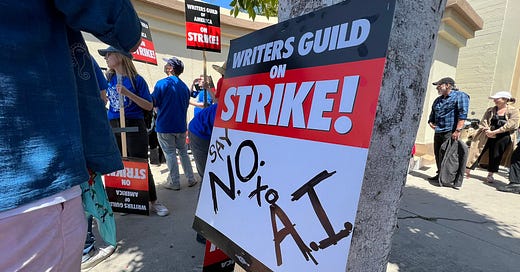

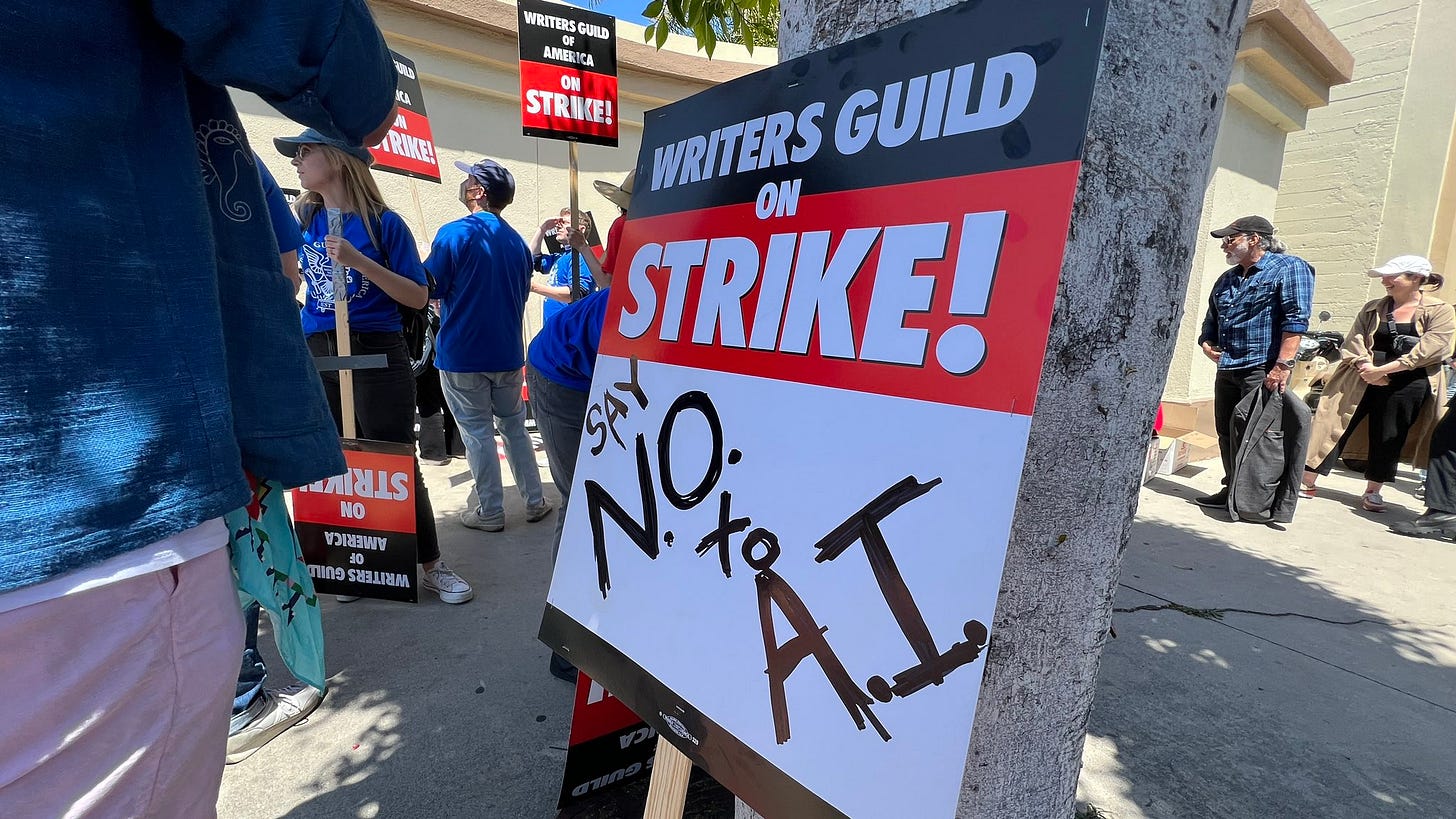

After this decades-long process of digitization, consolidation, and centralizing power on the part of major entertainment conglomerates, they’re wielding it to further transform the face of the industry and what it means to work in it. The Writers Guild is already on strike over residuals, working conditions, and have become concerned about the threat posed by AI writing tools. SAG-AFTRA, the actors’ union, is also seeking a strike authorization mandate from its members as it faces similar challenges with residuals and the threat of AI.

In recent years, Disney has been resurrecting dead actors or recreating younger versions of living actors as part of its Star Wars films and television shows, and signed a deal last year with James Earl Jones to use AI to continue generating his voice for future appearances of Darth Vader. Voice actors have found their contracts are increasingly including clauses that allow clients to generate their voices with AI, sometimes even without additional compensation, while others have already found websites generating their voices without their consent.

In the UK, performers union Equity is campaigning for laws against synthesizing performers voices and likenesses without their permission. As part of that campaign, actress Talulah Riley said, “As a performer, it is vital that my voice and my image are my own, no matter how easily and cheaply those things can be digitally replicated.” Last year, a deepfake of Bruce Willis was used in an advert for Russian telecom company Megafon, kicking off a discussion about the ethics of those technologies.

Commenting on that event, Reeves told Wired earlier this year, “If you go into deepfake land, it has none of your points of view. That’s scary.” But he also warned about the often unacknowledged power grab that comes with these technologies. Some of the things AI tools generate might seem fun, he said, but “there’s a corporatocracy behind it that’s looking to control those things.” That’s exactly what we see through the process of the digital transition.

AI builds on previous developments to continue shifting power toward corporate executives and away from the people making film and television. Executives want to use AI to generate scripts, even if that means further degrading the quality of culture, and they want to use it to continue the process of divorcing the actor from their performance — so it can be changed as much as executives want in post. Visual effects is already displacing craftspeople, and AI could start to take over some of the tasks currently done by effects workers. In December, director Guillermo del Toro told Decider, “I consume and love art made by humans. I am completely moved by that. And I am not interested in illustrations made by machines and the extrapolation of information.” Legendary filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki has gone so far as to call AI animation “an insult to life itself.”

AI isn’t democratizing anything. Its latest generative iteration depends on massive centralized computing power trained on an unimaginable amount of data scraped from the open web without permission or compensation. It will serve executives and management, not workers or the wider public, and deserves to be challenged.

Stop tech that doesn’t serve us

In Progress Without People: New Technology, Unemployment, and the Message of Resistance, David Noble makes the point that technological development is a political process shaped by powerful people. It’s not a linear process, and it isn’t just concerned with efficiency or profit. In fact, it might even work against those goals, because maintaining and increasing control over workers and production is paramount.

As anyone who has ever worked for a boss understands too well, management is concerned with one thing above all else, and that is staying in control. However much this control might be justified in the name of economic efficiency, with the self-serving claim, belied by nearly every sociological study of work, that centralized management authority is the key to productivity, the truth of the matter is that control is less a means to other ends than an end in itself.

In the film industry, digital technology has been rolled out over decades as part of a deliberate project to increase the control of major studios, and more recently the tech companies who entered during the streaming boom, over every other part of the industry, particularly cinemas and workers. But unlike in many other sectors, most workers in film and television are represented by strong unions that give them an uncommon degree of leverage to push back against the ongoing effort to restructure their industry and rob them of what power they have left. That’s why the writers’ strike and organizing elsewhere in the industry is so important.

But ultimately, halting these trends may require more than that. The last time the studios had such an immense degree of power over the entire industry, the government had to step in to rebalance the playing field. Today we might need something similar, pushed not just by organized film and television workers and their unions, but a wider public standing in solidarity with them and learning the lesson of the Luddites: that when technology is used against us, we have a responsibility to rise up against it.